Black Forum

by Pat Thomas

Has “revolution”—the word itself—lost its edge? For a long time now, advertisements have informed us about revolutionary hair sprays and automobiles. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, there were a number of revolutions taking place and none of them were going to make your hair smell terrific or provide a more comfortable driving experience. My book Listen, Whitey! is about how Black Power influenced folk, rock, soul and jazz between 1965 and 1975 when musicians were viewed as revolutionaries and revolutionaries were considered pop culture icons. Where Bob Dylan intersected with Huey P. Newton (the influence flowing in both directions), John Lennon hung out with Bobby Seale and Mick Jagger recorded a song about Angela Davis.

During the formative years of writing my book, I was honored to befriend David Hilliard and Elaine Brown, as well as meet Bobby Seale, Ericka Huggins and other former Black Panthers living in Oakland—all of whom inspired me.

The Black Panthers are interchangeable in many people’s minds with Black Power. The voices and images of Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver, David Hilliard and Elaine Brown are as symbolic of the sixties as John, Paul, George and Ringo. And like the individual Beatles, the Panther leaders often had differing political ideologies and separate agendas. Yet, the Panthers were just one of many Black Power groups (although the most important and influential).

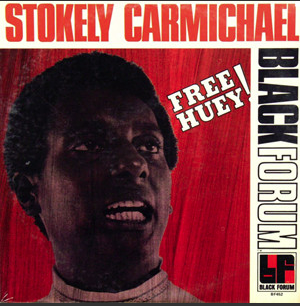

Far too often, the various personalities and organizations get lumped together. A victim of pop culture’s love of radical chic, Angela Davis (a member of the Communist Party) is often mistaken for a Black Panther. Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee enjoyed a brief coalition with the Black Panther Party, but had their own ideals and goals. Amiri Baraka aligned himself at various times with the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X and Ron Karenga’s US, but ultimately his legacy is co-founding the Black Arts Movement.

It’s important to recognize key differences separating the Panthers from Black Nationalists. My book attempts to dispel the myth that The Panthers were anti-white. In fact, some of their financial support came from Bert Schneider, executive producer of the hippie classic Easy Rider, one of the highest grossing films of the 1960s. Schneider funneled part of his millions of dollars of revenue from pop culture marketing into maintaining Huey P. Newton’s so-called “subversive” activities.

Black Nationalists were prone to wearing dashikis and taking African names. The Panthers did not. While the Panthers and the Black Nationalists shared a desire of independence from white society, the Panthers always remained multicultural, encouraging the alliance of all non-whites. The Black Nationalists focused on a strong African identity, maintaining a cultural connection to their native origins. Black Panther Huey P. Newton loved the music of Bob Dylan, while Black Nationalist Amiri Baraka debated if certain blues and jazz music was black enough to listen to.

The phrase “Black militant” gets thrown around a lot. Yes, there are photos of beret-wearing, shotgun-carrying African-Americans to back that up. Yet more people used a pencil, a book of poetry, a typewriter or a musical instrument to evoke change. But those images don’t make for good press. The Black Power Movement was not just political, but about humanity, about a way to live. Militancy is a label put on a group of people who simply wanted their equal rights.

With all that in mind, I recently had a detailed conversation with Aaron Dixon, who was a key member of the Black Panther Party from 1968 until well into the 1970s. He actually started the Seattle chapter in ’68 and went down to Oakland for training where he was lucky to study with Huey Newton, Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver that year – before they all went their separate ways. He also was able to spend time in Chicago with Fred Hampton before Fred was brutally assassinated by the FBI and police. He spent the late 60s and early 70s running the Seattle chapter – then he moved to Oakland to spend the bulk of the 1970s assisting Elaine Brown—who not only became the only woman to lead and run the Black Panther Party (after Huey was exiled to Cuba)—she became the only Black Panther to record for Motown! More on that below.

Aaron’s adventures can all be read in his enlightening (and ego-less) memoir: My People Are Rising: Memoir of a Black Panther Party Captain—I strongly suggest you seek that out. More urgent and more topical however is a conversation that I recorded on June 15th 2020 about the protesting across America which Aaron endorses and we compared the Black Lives Matter movement to what the Panthers struggled with during their heyday. (Although this is a Facebook link – you do NOT need to log onto or join Facebook to watch it – it can be viewed easily by all who click.)

Along the way, popular musicians picked up the mantle: Curtis Mayfield, Jimi Hendrix, Marvin Gaye, Nina Simone, James Brown, the Isley Brothers—even Graham Nash of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, who released a pop song about Bobby Seale being “bound and gagged” at the Chicago 8 trial.

New artists like the Art Ensemble of Chicago emerged, changing the face of jazz—while established musicians such as Max Roach changed direction and reflected the events around them. Albums by female poets Nikki Giovanni, Jayne Cortez, Maya Angelou and Sarah Webster Fabio shed new light on Black consciousness. Comedian Dick Gregory released albums that were entertaining, but as hard-hitting as the Black Panther Party newspaper. Religious leaders jumped into the fray as well. Reverend Jesse Jackson’s album included photos of him hanging with Amiri Baraka and Fred Hampton. Aretha Franklin’s father C.L. Franklin put a sermon to wax titled “The Meaning of Black Power.” The movement also responded regionally with 45rpm singles of protest music cropping up on small labels in Austin, Milwaukee, Chicago and Birmingham. Meanwhile, the Watts Prophets and Last Poets laid the groundwork for the emergence of rap a decade later.

Between 1965 and 1975, Black Power grew from a social-political underground movement into a significant force in American pop culture.

Stokely Carmichael’s Black Power speech in the hot Southeastern summer of 1966 was followed by the formation of the Black Panther Party in the fall of that year in Oakland. On Oct. 16, 1968, at the Olympics in Mexico City, Tommie Smith and John Carlos (two of the world’s fastest sprinters at that time) won the gold and bronze medals in the 200-meter race. After receiving their awards, they stepped onto a multitiered podium on the grounds of the Olympic stadium. As the American National Anthem began to play, Smith and Carlos bowed their heads and then, with each of them wearing one black glove (Smith on his right hand, Carlos on his left), they raised their fists high in the air, giving the entire Olympic stadium and an estimated television audience of 400 million people the clenched fist Black Power salute.

A renowned photograph of that moment has been reproduced countless times in the decades since as an indelible statement of Black Power—including the Oct. 26, 1968, issue of the Black Panther Party newspaper, published just 10 days after the event.

Such was the growing popularity of the Black Power clenched fist that the August 1969 issue of Liberator (a political magazine) featured an advertisement from TCB Products that for $4.50 would sell you a 6-inch high “Power Symbol” fist that was hand-carved in mahogany. For $5.75 you could purchase a 9-inch version—add 50 cents for postage and handling.

Another classic image of Black Power is the 1967 photo of Huey P. Newton sitting in oversized wicker chair, wearing the Panther uniform of a beret and leather jacket, holding a shotgun in one hand and a large African spear in the other. Thousands of these posters were distributed by the Black Panthers to fuel the “Free Huey” campaign following Newton’s arrest for the October 1967 shooting of two Oakland police officers.

As a result of the shooting incident, Newton was convicted of manslaughter and after a lengthy and much publicized legal battle, was ultimately acquitted and released in August 1970. The iconic image of Newton sitting in the wicker chair has been reproduced numerous times as a poster and in various publications since then. It is without a doubt the single most famous photograph of any Black Panther member.

By 1970—probably to the chagrin of Huey P. Newton—the black beret entered the pantheon of mainstream American pop culture: the weekly television sitcom, via the white bread musical comedy show, The Partridge Family. In “Soul Club,” broadcast on Jan. 29, 1971, the loveable, all-American Partridge Family find themselves in Detroit to perform in a club run by Richard Pryor and Lou Gossett, Jr. Keith Partridge (David Cassidy) writes a new “Afro-styled” pop tune in celebration of the family’s newfound surroundings, but the song requires a horn section and conga drums. Freckle-faced Danny Partridge convinces the local chapter of the “Afro-American Cultural Society” to come to the rescue with their members who play horns and drums. The Partridges and faux-Panthers perform Keith’s song together as part of a ghetto street fair. As the episode comes to a close and the family is boarding their bus in search of more fun and games, one of the “Afro-American Cultural Society” leaders arrives at the last minute to present Danny with a beret and announces honorary membership. Danny suggests that he open a local chapter when he gets back home, and everyone laughs. In 1997, TV Guide picked this episode as number 78 in the 100 Greatest TV episodes of all time (along with other wacky events such as Andy Warhol appearing on Love Boat). In the words of TV Guide, “This may be the most outlandish episode on our list; it’s certainly one of the best-intentioned.” Say what!?!

Motown’s subsidiary Black Forum label remains obscure. No Black Forum recordings have ever been included in any Motown label anthology. Power To The Motown People: Civil Rights Anthems and Political Soul 1968–1975—a 30-song, double-CD released in 2007—includes no Black Forum artists. (The label goes unmentioned in the booklet’s overview of Motown during the Black Power era, and in most histories of Motown). The cover features a clenched fist salute as its main artwork and a photograph of Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale are inside the jewel case. But Elaine Brown and Amiri Baraka both released albums of songs (not speeches) on Black Forum during the period covered by the compilation.

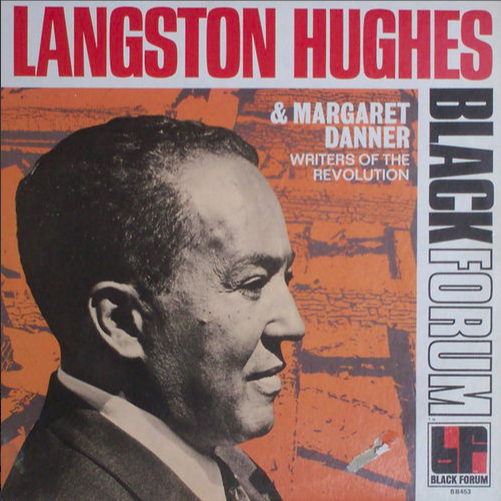

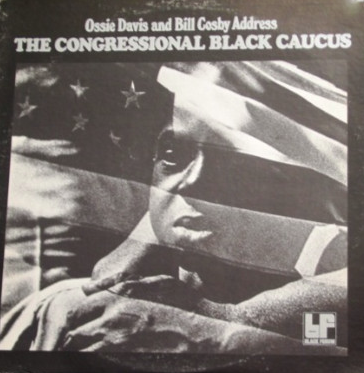

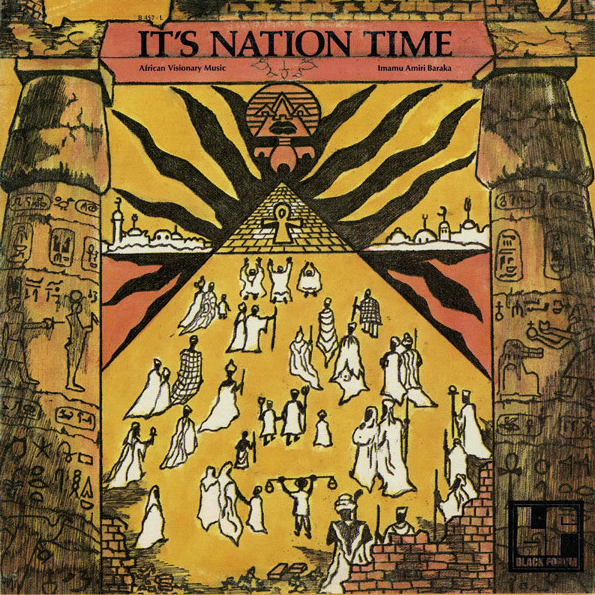

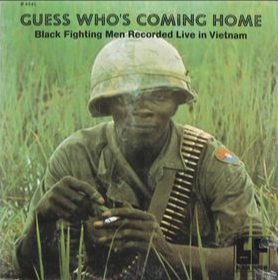

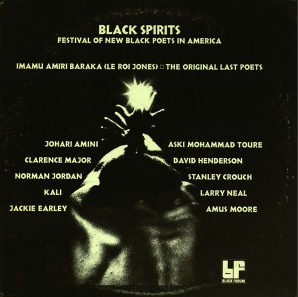

The label released eight albums between 1970 and 1973: a speech denouncing the Vietnam War by Martin Luther King Jr., a very heated address on race relations by Stokely Carmichael, and interviews with black soldiers fighting in Vietnam conducted by a Time magazine correspondent; a narrative by writers Langston Hughes and Margaret Danner; an LP of poetry including Amiri Baraka, members of the Last Poets and Stanley Crouch; an album of songs featuring Amiri Baraka as a vocalist backed by free jazz musicians. The final two releases were Ossie Davis and Bill Cosby speaking in front of the first Congressional Black Caucus and Elaine Brown’s aforementioned LP.

Let’s dive in to Black Forum’s catalog, shall we?

Amiri Baraka out-grooves the groovers—accompanied by James Mtume, Idris Muhammad, Lonnie Smith, Gary Bartz and Gwen Guthrie.

*who were then one-half of The Corporation™ production team + created a string of hits for the Jackson 5.

MLK’s speech against the "triple evils of racism, economic exploitation, and militarism," released by Black Forum records (Excerpts from a sermon at the Ebenezer Baptist Church, April 30, 1967.)

Recorded Live at the Apollo Theater in 1971, Produced by Woodie King, Jr., the poetry festival included Imamu Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), Kali (daughter of authoress Verta Mae Grosvenor), James W. Thompson, Norman Jordan, Aski Mohammad Toure, Jayne Cortez, Jackie Earley, Rhonda Davis, Johari Amini, David Henderson, Don L. Lee, Quincy Troupe, Ed Bullins, Nikki Giovanni, Sonja Sanchez, Carolyn M. Rodgers, Larry Neal, Keoropotse Kgositsile and The Original Last Poets.

Pat Thomas lives and works in Los Angeles