A Canticle for Gary Burger

The Monks were a real band before they

became brainchildren of German art students-turned-ad men Karl Remy and Walther Niemann. They were the 5 Torquays—a Gelnhausen bar band. All five were American GIs.

“We have listened to you,” Remy and Niemann said to the Torquays. “You will play the music of the future.”

According to the Remy and Niemann, the future would be hard and would not be beautiful, with music to match. Under their guidance, the Torquays remade themselves into “anti-Beatles.” They renamed themselves. They dressed up like medieval friars. They got tonsures.

The music of the future would not include blue notes and bent guitar strings, so the Monks did away with all that. They cut covers out of their sets—no more Chuck Berry; no more Elvis Presley. That was the past. The Monks started writting their own songs. “10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

Blast off!,” one went.

Think about that for a moment. Consider those those tonsures.

“I’ve been credited with originating, back in 1973-74, the practice of deliberately wearing ripped clothes, sometimes further transformed with safety pins and drawing and words; with naming myself something negative on purpose; and with inventing the haircut that got identified with punk,” Richard Hell wrote a few years ago, in the catalogue for Punk: Chaos to Couture.

All of that’s basically true ... Without a doubt, though, the single most influential thing I’ve done is my haircut ... It’s sometimes said I based it on Rimbaud, but that’s not true. It came from analysing what made the two prior main rock and roll haircuts – Elvis’s and the Beatles’ – work. That line of thought led me to recall the boy’s do typical of my childhood, which was a short, stiff ‘butch’ or ‘crew’ cut that had gone to seed because kids don’t like going to barbers. When that patchy raggedness was exaggerated the way I exaggerated it, it looked defiant, even criminal. A guy with a haircut like that couldn’t have an office job. And no barber could even conceive of it. It was something you had to do yourself.

I’m not saying the Monks’ tonsures did the same thing. (A lot of Germans simply assumed they were monks. Which they were.) I’m not saying the Monks invented punk. Some of their music still sounds like the future; they’re a bit like the Silver Apples that way:

But a lot of it sounds like the Fugs:

No one outside of Germany heard them at the time. Eventually, Mark. E. Smith heard them:

But it’s not the Fall I think of when I think of the Monks. The way each new song articulates a new idea; economically, but with real force. That reminds me of Wire:

Then again, “Blast Off,” above, reminds me of Bo Diddley’s “Road Runner”:

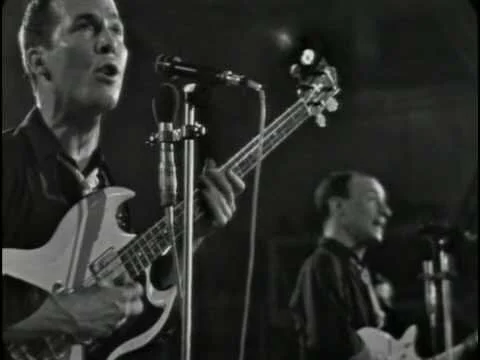

Here’s “Monk Time,” the first song from Monks’ first album, Black Monk Time:

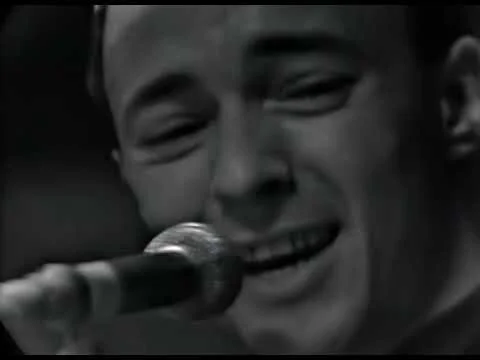

“Alright, my name's Gary,” Gary Burger sings. “Let's go, it's beat time, it's hop time, it's Monk time!”

You know we don't like the army.

What army?

Who cares what army?

Why do you kill all those kids over there in Vietnam?

Mad Viet Cong!

My brother died in Vietnam!

That’s striking, not because it’s so out there (Lenny Bruce was more out there), but because “Vietnam” was not a word you heard on rock and roll records issued by Elektra, or Capitol, or EMI, Decca, or anyone else. In Germany, on Polydor, the Monks got away with it. They released that one album, and then they broke up—on the eve of their first tour (of Vietnam, as it happens), after hearing that the Viet Cong had begun to lob grenades into bars and clubs frequented by American soldiers. Crowds were deadly. The Monks did not want to draw one and end up with blood on their hands.